Your one-stop shop for news, views and getting clues. I AM YOUR INFORMATION FILTER, since 2006.

Sunday, November 29, 2009

Screw the banks: Use cash

A Simple Plan to Screw Big Banking. Use Cash.

By Chaz Valenza

November 28, 2009 | Chaz Valenta

Here's a simple plan that will bring Big Banking to its feet: Use Cash.

For decades Big Greed has been selling us the idea that markets are just perfecto! Don't regulate them. Don't even bother chasing down fraud. "The Market" (Angelic Voices: Ahhhhh!) is so beautifully simple even scams cannot long survive.

Let's take the "Wisdom of The Market" stick it up Big Banking's rectum, twist, turn and otherwise shove vigorously and often.

Face it, the cavalry is not coming to the rescue if your name is not Goldman Sachs.

Government of the people, by the people, and for the people is temporarily out-of-order, like a soda machine that is taking dollar bills from customer after customer but relinquishes not one quenching 12 oz. can.

No legislation or regulations are in the offing to cap the rising tide of usury interest rates, curb punishing banking fees on debit cards or curtail demonic payday loans.

Here's the bill of fare:

Credit Card Interest: 30%

Merchant Credit Card Fees: 3.5 - 5%

Merchant Credit Card Receivables Loan: 36 – 97%

Payday Loans: 100 – 500%

Debit Card Overdraft Fees,

Over limit Fees, Late Payment Fees, etc:

Interest Equivalent to 12% - 300% and otherwise unlimited

Throw stones – millions of them. Every plastic transaction denied is a slice in the skin of Big Banking.

As a buyer: Use Cash. It's going to save you money verses paying with credit card or making a mistake with a debit card.

As a merchant: Discount 5% for Cash. It's going to save you money in reduced merchant charges and days waiting for credit card receivables. It's also an advantage against the Big Box stores and Big Food restaurants.

Think about it. Who would you rather have that 3.5% you give to Big Plastic on every credit or debit card transaction: Your customer or Big Banking? Isn't that worth the extra 1.5% in the discount?

But it gets better. It's guerilla warfare. It's a simple insurgency. Avoid the banking system to bring it to its knees. Use Cash.

How low-tech is this? How unstoppable? How inconvenient? Yes. But worth it!

Put it on bumper stickers. Make it your email signature. Pass the word in whispers to everyone who works for a living. Write it in magic marker on T-shirts. Design a flag and boldly embroider. Print up window signs. Post it on every blog you visit. Tweet it from the highest mountain. Two simple words: Use Cash.

Will they fight back? Of course they will. They will end Absolutely Free* Checking that is costing us all billions. They may lower their rates and switch up the penalty fee structure. They might even lobby for the end of printed dollars. That's how we'll know it's working!

Here's the future and the future is now. Personal loans? Small business lines of credit? Only to those who don't need them or at a killer rates of interest.

Use Cash.

Every cash transaction snatches a dime, a dollar, thirty-five dollars, a hundred dollars or more out of the greedy, blood soaked hands of Big Banking. Each transaction denied is a cut. Together it's death by a billion cuts daily.

5% Discount for Cash.

You'll be shooting at Big Plastic's feet. Smile as you watch 'em dance. They have us hooked on plastic. They claim it's faster, quicker, better. People spend more. Yes, they do. Until the abusive fees take your customers' last penny of discretionary cash and they're broke.

Debit or Credit, plastic is really just one thing: a cash substitute provided by a commission taking broker who charges you a fee at every cash register. They intend to milk it for all it's worth. Cut up your cards, today, right now.

And here's the beauty part: We don't need no stinking badges to fight back. Just: Use Cash. Wow! I'm starting to agree: The Market Rules!

Don't worry about freeing up credit or ending the banking abuse, etc. This is action you can take right now, and again and again, day after day after day.

Sure, there are bigger fish to fry: End the Fed, local currency, non-profit banking, total monetary reform, but this is something we can do right now.

It's easy, fast, effective: Don't give Big Banking any small change.

Yes we can nickel and dime the banks to death! Spread the word: Use Cash.

Chaz Valenza is writer and small business owner in New Jersey. He earned his MBA from New York University's Stern School of Business.

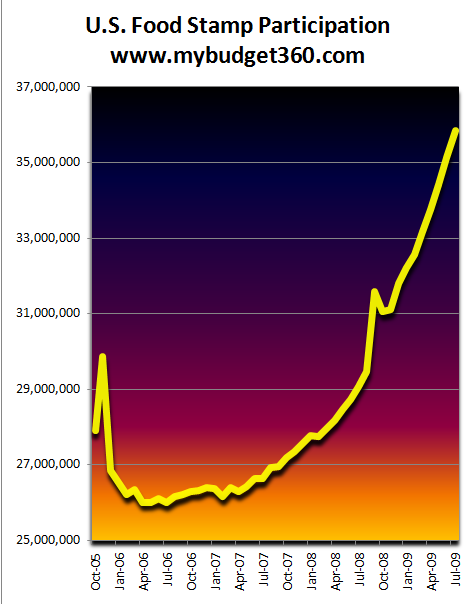

Thanks, Obama: 12% of Americans on food stamps

Meanwhile, the states, like drug dealers, are pushing food stamps on more and more erstwhile honest, hard-working, self-sufficient Americans, because unlike cash welfare payments, food stamps are 100% federally funded.

Even conservative and once proud Warren County, Ohio, which turned down federal stimulus funds on principle, has lately doubled its dependence on food stamps. Said proud, principled, Warren County Commissioner Dave Young [R]: "As soon as people figure out they can vote representatives in to give them benefits, that's the end of democracy. More and more people will be taking, and fewer will be producing." You tell 'em, Dave! ... I mean, wait! Don't tell them! You just helped the people figure it out! Nooooooo!.....

Seriously though, the following excerpt so neatly encapsulates everything that's wrong with white, middle-class, conservative Americans, who are getting beaten over the head by economic forces they can't control and yet oppose any programs or reforms designed to help them or their compatriots:

While Mr. Dawson, the electrician, has kept his job, the drive to distant work sites has doubled his gas bill, food prices rose sharply last year and his health insurance premiums have soared. His monthly expenses have risen by about $400, and the elimination of overtime has cost him $200 a month. Food stamps help fill the gap.

Like many new beneficiaries here, Mr. Dawson argues that people often abuse the program and is quick to say he is different. While some people "choose not to get married, just so they can apply for benefits," he is a married, churchgoing man who works and owns his home. While "some people put piles of steaks in their carts," he will not use the government's money for luxuries like coffee or soda. "To me, that's just morally wrong," he said.

He has noticed crowds of midnight shoppers once a month when benefits get renewed. While policy analysts, spotting similar crowds nationwide, have called them a sign of increased hunger, he sees idleness. "Generally, if you're up at that hour and not working, what are you into?" he said.

Note how even as he receives welfare, he can't overcome his hardwired angry-white-guy programming to criticize other people on welfare. Classic.

The Safety Net - Across U.S., Food Stamp Use Soars and Stigma Fades

By Jason DeParle and Robert Gebeloff

November 30, 2009 | New York Times

URL: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/29/us/29foodstamps.html?pagewanted=1&_r=2&th&emc=th

Mark Pittman (RIP) on mortgage crisis, Fed

By Ryan Chittum

February 27, 2009 | Columbia Journalism Review

(UPDATE, November 29, 2009: Mark died a couple of days ago. It's a huge loss and we'll have more on him next week, but until then you can read some of what we've written about his exploits here. We wrote about when he and Bloomberg sued the Fed and when he won. Here's Pittman with his friend and colleague Bob Ivry (who wrote Pittman's excellent obituary), with a great profile of Elizabeth Warren last week. Here's our look at how a Pittman story last September helped break the huge story of Goldman's (and others') backdoor bailout through AIG.

Here he is going after an incredibly complex story: How much are those toxic assets actually worth? And Pittman kept a close eye on the disastrously bad deals Uncle Sam cut for itself to benefit Wall Street. Watch him leverage the hot story, the AIG bonuses, to show how much bigger another story was, the bailouts of AIG's counterparties.)

Mark Pittman has been all over this financial crisis.

He was part of a team at Bloomberg News that won the Loeb Award last year for a five-part series on the origins of the crisis called "Wall Street's Faustian Bargain," including Pittman's lead story on how the Street goosed the subprime mortgage market late with financial engineering.

The new standardized contracts they created would allow firms to protect themselves from the risks of subprime mortgages, enable speculators to bet against the U.S. housing market, and help meet demand from institutional investors for the high yields of loans to homeowners with poor credit.

The tools also magnified losses so much that a small number of defaulting subprime borrowers could devastate securities held by banks and pension funds globally, freeze corporate lending, and bring the world's credit markets to a standstill.

In addition to the Loeb-winning work, Pittman has broken major stories on Goldman Sachs's interest in the AIG bailout, Hank Paulson's role in creating the subprime mess, and the ratings agencies inexplicable delays in downgrading mortgage securities, and he's delved into how Wall Street spread its detritus across the world.

Pittman is a native of Kansas City, graduated from the University of Kansas, and got his first job covering cops at the Coffeyville Journal in southern Kansas, where he was paid so little he had to get a part-time job as a ranch hand across the Oklahoma border in Lenapah. Proving yet again that it really is a small world and journalism is even smaller (and getting smaller every day, as Pittman points out) we discovered to our amazement that my late grandfather Arva Chittum was a good source of Pittman's back in the early 1980's in Coffeyville.

He spent twelve years at the Times Herald-Record in Middletown, New York, before joining Bloomberg News in 1997.

We spoke recently about cops, CDO's, and the crisis.

The Audit: How did you get started at Bloomberg News?

Mark Pittman: That was back when Bloomberg News only had like fifty people in New York. I covered oil in the beginning and then they moved me to covering securities firms. I was covering the Street in 1999 to 2000. There were only two of us covering the whole Street. We didn't do a very good job as you can imagine. We could barely get the earnings out.

I went on to private equity and corporate finance. I got a wide education. I learned a lot about trading. If you cover the oil markets, those guys know how to trade. They know how to pull the trigger on stuff and back out. That gets in your bones. When you realize how you make money doing that kind of stuff, a lot of other things make sense. I'm not sure that a lot of business journalists get that kind of knowledge.

That's stuff you just don't get covering companies or doing profiles. You learn different stuff.

TA: How'd you get onto the crisis story?

MP: I had a conversation with a couple of people in late 2006/early 2007, and people were talking about what's wrong with asset-backed securities and where all this is headed. I'd also covered derivatives contracts. When they first started doing credit-default swaps on companies, I covered that. That was like '99-2000. You could tell it was going to be a really hot thing.

When they started talking about doing derivatives on mortgage-backed securities [a bet against the housing market; this is explained a few lines below], I was like "oh, man, that means the banks are scared!" That was 2006, and we wrote a whole series about this.

You always want to be around the hot story. If you're not around the hot story, you're screwed.

TA: So did you go into that pretty much full-time? How'd you convince your editors to let you do that?

MP: You know it really wasn't hard. They've really let me take a lot of chances here, and they're extremely generous with my time. They recognize it as an important part of the reporting process. They give me a lot of rope. They let me figure stuff out. That's something that's in real short supply with a lot of news organizations now. You've got to let reporters run and figure out what's going on.

TA: Not many others have the resources to do much of that nowadays.

MP: Instead of doing the sixth sidebar on a bailout program that probably won't work anyway, let the person figure out what's actually happening. And you've got to let your people do that.

We did a five-part series [the one that won the Loeb] on the whole idea of why the subprime crisis occurred, and it starts with this story about how a bunch of traders at Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan got together and said "We need a standard contract to be able to short the mortgage market." As soon as I realized they were going to try and short the mortgage market I said, "Ohhh. That means they think the market is going down."

TA: And these are the guys who've come out pretty okay in this.

MP: You'll notice UBS and Merrill aren't in the group. The thing about this entire series of events is this is so complicated and so intertwined that we don't have —journalists are not qualified to cover the story. We don't have the background. These guys are doing stuff that you had no idea was happening. The off-balance-sheet accounting stuff is crazy.

TA: Well, if the ex-chairman of the Fed Alan Greenspan, formerly regarded as a near god, didn't understand what this stuff was, who did? He had access to all the people and all the information he could want.

MP: He had no idea what was going on. How is it possible for them to sell themselves, to an off-balance-sheet entity, risk that is now exploding all over everybody? Why would that be allowed and why would you be able to book a profit on this? Who was in charge of this?

We haven't got to the bottom of this whole thing yet. Somebody's going to do this big forensic—and it might be me!—somebody's going to do the deep dive into how everything happened and they're going to find out that this system was just on autopilot and was spinning money out to a whole bunch of people. And it included you and me.

TA: In the form of cheap credit?

MP: Yes. The spreads should never have gotten to that level.

This goes back to why AIG is all screwed up. The banks sold AIG all their risk in 2007, when it was really blowing up. AIG had sworn that they weren't going to do any more of this and then (the banks) restuffed the CDO's [collateralized debt obligations] with new stuff. So (AIG) had newer collateral that they weren't really aware of.

TA: So the banks were stuffing the CDO's with new stuff but AIG didn't know they were replacing the stuff?

MP: Right.

TA: An MBS [mortgage-backed security], you can't move things in or out, but a CDO you can. Are the banks liable for this? AIG got blown up, but these guys knew what they were doing.

MP: You know what, the lawsuits will have to sort that out. And it's going to be going on for years. It's going to be just a debacle. Congress is going to have go through and force people to say "Okay, so what did you do with this, and where did it go from here?" They need to have very talented investigators go in and find out what the deal is.

TA: Tell me how your cops background plays into what you're doing now.

MP: You end up with a big BS detector as a cops reporter because the cops lie to you, the victims lie to you, the people helping the victims lie to you. And you've got to sort through and there will be a story that seems a certain way and it just won't be—and you know it. That's what this is about.

The reporters who didn't question the tight, tight spreads [the narrow difference in interest rates offered by Treasury bills and other, less secure instruments] that were going on in corporate [bonds], it was wrong. Where is this demand coming from? How can you guys sell this issue in thirty minutes? Who the hell's buying this stuff like that? We're going to come to the answer that it was going off balance sheet, at least temporarily, and then it might be sold to other customers.

TA: So they were buying it themselves and…

MP: They were buying it themselves. Yeah. And not every deal. But you know what—it happened enough. We don't have enough journalists in America who understand what a spread does, which is the essence of banking. I just finished Dean's piece in Mother Jones recently. We've got 9,000 business journalists and maybe twenty of them know what a spread is. This is not business journalism's finest hour. But it is our biggest opportunity ever.

TA: How does the Bloomberg terminal inform your reporting or help you find leads?

MP: Well, I'll give you an example. The first best story that I did about this—I'm gonna brag about this—was in June of '07. It said that subprime bonds are failing and they're failing at an alarming rate, and they're going up a lot, and they all need to be downgraded. The ratings companies aren't following their own criteria for what makes a bond a certain rating. I did that through data that's available on the Bloomberg. We've got a function called DQRP, which gives you delinquency reports on every RMBS [residential mortgage-backed security], dividing it up by category. So you can pick the worst bonds with the worst stuff and you can divide it up by rating—all kinds of sorting. Nobody has that but us.

TA: I didn't even know that capability was out there.

MP: Hell yes, man. And it works. Then you can pull up each individual bond and you've got a complete description of its geographic reach—how much is in California, all kinds of great stuff. What a weapon! And if you know how to use it, it works pretty well.

TA: So what's your prescription for business journalists? What do they need to know and do? Not everybody's going to have a $20,000 a year Bloomberg terminal to play with.

MP: Hardly anyone has a Bloomberg machine and the ones that do don't know how to use it.

But you know what? The government needs to make this kind of data much more publicly available than it is now. We purchase a lot of this. But, for instance, a lot of the bond deals were (not subject to disclosure). And all the CDO's were private placements. We know why—because they placed them with themselves. The number of secret deals going bad is astounding, it's probably 90 percent of them were secret deals.

TA: Bloomberg's got a ton of people on bonds, but I've said before that a part of why the business press failed here was that it has so many times more people covering equities than debt. And debt markets are many, many times the size of the equity markets. That's kind of a major problem right there, right?

MP: It is huge. Most reporters, it's shocking how few of them actually understand the difference between price and yield. Hardly any business journalist actually covers the financing. If you cover a company and all of a sudden their borrowing costs go from 100 (basis points) over to 250 or 300 over [meaning investors believe the risk has increased substantially], and no one asks a question. There's a problem there when that happens and nobody asks a question. I think we have training issues in a huge way in our profession. We brought a knife to a gunfight.

TA: Does there need to be regulation just to simplify things to where it makes sense to more people?

MP: If it was all transparent the complexity wouldn't matter. If the CDO market had had publicly available prospectuses with the contents of the CDO disclosed, we wouldn't have this issue, because Bloomberg probably would have made fun of anybody who bought anything like this. But there was this enormous shadow banking system going on. We did a series about that, too. A lot of times people don't see what we do.

TA: That's one of the problems I've noticed. We've consciously tried at The Audit to make sure people are reading your stuff. I don't think it's become a habit for a lot of people even in the biz to go over to Bloomberg.

MP: It kinda bums you out, because you want to do things that have big (impact) because that's why you're in the business. And public policy would work a lot better if they actually understood what the hell was going on.

TA: Like adding up the total number of trillions that the government is on the hook for in this bailout. Nobody else is doing that but you. Why not?

MP: Because it's a big pain. You start off with whatever you can remember off the top of your head—oh, they're doing this, they're doing that—you start writing it down on a piece of paper and you go "Wow, this is real money." It starts adding up.

The thing that people don't realize is that the Fed is now the "bad bank." That's just something that people don't understand. They've taken collateral, and they refuse to tell us how they valued it…

We have numerous banks— dozens, maybe hundreds that are insolvent. And they become more insolvent every day because more people quit paying their mortgage loans, and more guys move out of the shopping center, and more people quit paying their credit cards. But nobody wants to have the adult conversation…We need to be honest about what the problem is here, how big it is, and how we're going forward to clean it up, and who's going to pay for it.

TA: Basically the charade that's going on here is that they haven't marked these assets down yet because that would show they're insolvent.

MP: But a lot of [the assets] have gone to the Fed, though, as collateral for loans. They're still on their balance sheet, but you borrowed against them. We don't know if those are cracked CDO's or prime RMBS…

TA: That's what you guys are suing (the Federal Reserve) for—to find out what the collateral is.

MP: Yeah, and that's the secret part of the story that nobody wants to let you know.

TA: Because it's worth pennies on the dollar or dimes on the dollar.

MP: Yeah, and then everybody's going to go "Oh my God, we're lending ninety cents on something that's worth twenty or thirty?"

TA: They say they don't want to disclose it because it would interfere with the markets, is that right?

MP: Their basic argument is this would cause chaos, and they're probably right. But that doesn't mean that the American taxpayer ought to be on the hook for this.

TA: Why would it cause chaos?

MP: Because people would realize that we're lending eighty cents on the dollar for something that's worth twenty cents.

TA: So political chaos?

MP: And maybe market chaos, too. Well, you know the market's probably pretty savvy about this thing, and everybody knows what's going on but we just haven't communicated with the public. When you say "political chaos" you might well be right. That may be what it was. Congress is going to go "We're lending this much money on this Triple-C security? What are we thinking here?"

TA: One thing I really like about you guys is in your reporting and writing, you have a sense of outrage that's not in the Journal, say. This thing is so huge, and you guys are conveying the magnitude of it better than some, and there's a sense of urgency that's lacking elsewhere. Is this a conscious thing in the newsroom?

MP: We have been primary movers for transparency in markets since our existence. Bloomberg's reason for being was to give the buy side enough tools so they wouldn't get screwed by the investment banks. That's what we're about. So we're a weapon for the buy side and a de facto weapon for every one who has a mutual fund. We just need to level the playing field and let everybody know what's going on. This is from Matt Winkler on down. This is what we do.

It's also that we realize this is a defining moment for business journalism and for Wall Street. I think that this organization, this news department, was built for this crisis. We've got more tools than anybody, we've got the will, we have the assets to go after this in a huge way. Everybody believes that in this room.

Hopefully, we will be able to inform the people enough to know how badly we're getting screwed (laughs). We need to know how to prevent it from happening again, and we need to know who did it. There's renewed energy on this front because we've staffed up the people who cover banks, the securities firms. We have a lot more people going at real estate and a bunch of different areas that this involves. That was a conscious move from meetings we started having in 2007. We hired people and we moved people from one area to another area.

Our issue is we have readers who are very interested in very small things. That's why they have the terminal. It's because they're interested in natural gas or things that aren't connected with the biggest story in twenty years, maybe longer. This is a big deal and it's going to be going on—I swear to God I'm going to retire on this story, because it's just going to keep happening.

Saturday, November 28, 2009

No Islamo-terrorism to see here, just another ordinary day....

November 26, 2009 | Associated Press

Friday, November 27, 2009

Germany's top general resigns over Afghan coverup

It's interesting -- and heartening -- that the German people are so concerned about the fate of innocent civilians in war. What did Germans learn from WWII that we didn't?

Germany's highest-ranking soldier has resigned over allegations that the Defense Ministry did not come clean about civilians killed in a recent air strike in Afghanistan. Former Defense Minister Franz Josef Jung is also under pressure to resign.

November 26, 2009 | Speigel Online

URL: http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/0,1518,663582,00.html

Obama's emissions targets not so costly after all?

More good military news: Divorce rates higher than ever

Military divorces edge up again in 9th year of war

By Pauline Jelinek

November 27, 2009 | Associated Press

Reagan not Reagany enough for pro-Reagan RNC?

- "Where's the Reagan?"

- "A Reagan is forever."

- "Obama: The un-Reagan."

- "Got Reagan?"

- "Think outside the Reagan."

- "They're R-r-r-eagan!"

- "The few, the proud, the Reagans. (Except Ron, Jr.)"

- "Yo quiero Reagan."

- "We make Reagan the old-fashioned way -- We Reagan it."

- "Don't get mad. Get Reagan."

- "(Reagan) Lifts and separates."

- "Get a piece of the Reagan."

- "Leave the Reagan-ing to us."

- "Reagans wanted."

- "(Reagan) The king of presidents."

- "When it absolutely, positively has to be Reagan."

- "Once you Reagan, you can't stop."

- "Did somebody say Reagan?"

- "It's not your father's Reagan."

- "Reagan's number two; he tries harder."

- "Is it live, or is it Reagan?"

- "I'm Reagan, and I can't get up!"

"Republican solidarity in opposition to Obama's socialist agenda is necessary to preserve the security of our country, our economic and political freedoms, and our way of life."

WHEREAS, the Republican National Committee shares President Ronald Reagan's belief that the Republican Party should espouse conservative principles and public policies and welcome persons of diverse views; and WHEREAS, the Republican National Committee desires to implement President Reagan's Unity Principle for Support of Candidates; and WHEREAS, in addition to supporting candidates, the Republican National Committee provides financial support for Republican state and local parties for party building and federal election activities, which benefits all candidates and is not affected by this resolution; and THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED, that the Republican National Committee identifies ten (10) key public policy positions for the 2010 election cycle, which the Republican National Committee expects its public officials and candidates to support: (1) We support smaller government, smaller national debt, lower deficits and lower taxes by opposing bills like Obama's "stimulus" bill; (2) We support market-based health care reform and oppose Obama-style government run healthcare; (3) We support market-based energy reforms by opposing cap and trade legislation; (4) We support workers' right to secret ballot by opposing card check; (5) We support legal immigration and assimilation into American society by opposing amnesty for illegal immigrants; (6) We support victory in Iraq and Afghanistan by supporting military-recommended troop surges; (7) We support containment of Iran and North Korea, particularly effective action to eliminate their nuclear weapons threat; (8) We support retention of the Defense of Marriage Act; (9) We support protecting the lives of vulnerable persons by opposing health care rationing, denial of health care and government funding of abortion; and (10) We support the right to keep and bear arms by opposing government restrictions on gun ownership; and be further RESOLVED, that a candidate who disagrees with three or more of the above stated public policy positions of the Republican National Committee, as identified by the voting record, public statements and/or signed questionnaire of the candidate, shall not be eligible for financial support and endorsement by the Republican National Committee; and be further RESOLVED, that upon the approval of this resolution the Republican National Committee shall deliver a copy of this resolution to each of Republican members of Congress, all Republican candidates for Congress, as they become known, and to each Republican state and territorial party office.

Of course it is true that Reagan, like John Kerry, was for some ideas before he was against them.

Bailed-out AIG soaking poor rural Kentuckians

ClimateGate! Gotcha! Ka-Pow!

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Taibbi: Palin is politics' first WWE star

Ex-Scotland Yard cop turned Birther leader

The former British police officer who wants to bring down Barack Obama

Conspiracist prominent in movement claiming president is an imposter

November 23, 2009 | The Guardian

Neil Sankey has spent his life investigating organised crimes. As a former British police officer with almost 20 years experience, he was seconded to elite units of Scotland Yard through most of the 1970s and now runs his own private detective agency [http://www.privateinvestigation.com/] in California.

Over the years he has been involved in some big investigations. As part of the Special Branch and Bomb Squad he monitored British leftwing groups and the IRA, and in America his clients have included several big car companies.

But never has he handled anything quite as monumental as the investigation that is absorbing his energies today.

Sankey is pursuing what he believes to be fraud on a gigantic scale ? a conspiracy, no less, to infiltrate and destroy the free world by putting a foreign imposter into the White House.

Sankey is a member of the fringe alliance known widely as the Birthers (he dislikes the expression, considering it pejorative). Together with other activists, he seeks to prove that Barack Obama is not a true American and is therefore ineligible to be president.

Over the past year Sankey has been at the centre of some of the most aggressive efforts by the Birthers to unseat the president. At the end of last year he tried to block Obama's inauguration by contacting all 538 electoral college representatives who formally elect the president. More recently, he has carried out his own probe into Obama's personal identification history which has revealed, he believes, a suspicious multiplicity of social security numbers.

Sankey says his fascination began with the realisation "that this man wasn't what he said he was. He wasn't an ordinary Democrat ? he was far more extreme than that." So about a year ago he began reading blogs and websites that claimed to expose Obama's foreign roots, his spurious Hawaiian birth certificate and the $2m White House cover-up that has prevented the public finding out about the plot.

His travels put him in touch with Orly Taitz [http://www.orlytaitzesq.com/], one of the most energetic and flamboyant of the Birther leaders. Of Moldovan extraction, she emigrated via Israel to California where she works as a dentist and lawyer. She has filed numerous legal suits around the country on behalf of serving US military personnel attempting to prevent their deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan on the grounds that they should not be taking orders from an illegally serving commander-in-chief.

Sankey's journey from having worked in some of the most elite police units in Britain to taking part in a movement dedicated to the pursuit of a paranoid conspiracy theory may seem bizarre. But he insists it has been a natural progression. He joined the Hampshire force in 1961, and was seconded as a detective sergeant to Scotland Yard where he developed a specialism tracking leftwing political groups and the IRA.

"We created an operation into what we called revolutionary criminality ? monitoring leftwing bookshops and extremist literature, following the leftist fringe and the Marxist links of the IRA."

In 1980 he moved to California, set up his agency, and became a naturalised American in 1985.

Sankey contends that his police experience in England now informs his fight against Obama. "It's quite obvious to me - America is heading towards a socialised state just as has happened in Europe. Socialised medicine, everyone on the dole, and when everything collapses you tip the scales into Marxism."

He also believes his training in Scotland Yard is now reaping benefits for the Birthers. The same techniques he used to analyse the IRA's associations he is now applying to Obama. Most recently, he carried out an exhaustive search of databases that he claims threw up 140 different identification numbers and addresses for "Barack Obama". He admits the findings prove nothing ? there is nothing to link the entries to the president ? but he believes it raises further doubts that need investigating.

Taitz says Sankey's UK police expertise has been invaluable. "He has had superb training. I have the greatest respect for Scotland Yard."

The Birther movement is not a unique phenomenon within US politics. Bill Clinton was accused by conspiracy theorists of having murdered his friend and White House legal adviser Vince Foster; George Bush had to contend with the Truthers who believe he was the mastermind behind the 9/11 attacks.

But the Birthers are unlike previous movements in that they are focused on who Obama is rather than what he does.

"There is no other president who has had his citizenship questioned in this way," says Patricia Turner, an expert in folklore at the University of California, Davis. Turner says that the popular Birther theories that Obama has used fake Hawaiian documents to disguise the fact he was born in Kenya or Indonesia are retellings of an old story. "This is just a proxy for old-fashioned racism. They are driven by hostility towards anything they see as foreign or exotic."

Although the Birthers are on the fringe of American politics, they are part of a wider surge of rightwing anger towards Obama's perceived socialist policies that is sweeping the country.

As such they can command considerable support. An internet petition [http://www.wnd.com/index.php?fa=PAGE.view&pageId=81550] demanding an official inquiry into Obama's origins has been signed by almost 500,000; critics say the number is inflated by multiple clicks.

Like any virulent conspiracy theory, that of Obama's birth has proved immune to the intervention of fact. When Obama's birth certificate in Hawaii was digitally scanned for all to see, it was denounced as a forgery. The birth notices printed by two Hawaii newspapers announcing his birth in August 1961 were similarly dismissed.

Dozens of legal actions have been brought before the courts by Taitz and other Birther leaders, and so far every one has been thrown out. Last month a federal judge dismissed Taitz's lawsuit seeking to challenge the chain of military command up to Obama as commander-in-chief. In a devastating ruling, the judge accused Taitz of trying to "emasculate the military" in a way that would "leave this country defenceless".

None of these setbacks have dissuaded Sankey. He says accusations of racism are smears that he has come to expect. "The objection is not Obama's colour but his politics. I like him as a person, I just wish he was genuine."

[Yeah, Sankey likes Obama, he just believes Obama's a crypto-Marxist bent on destroying America. What's not to like? Jeeez. - J]

Sunday, November 22, 2009

Teabaggers feuding, heading toward the end

Economists agree stimulus was too small, but worth it

By Jackie Calmes and Michael Cooper

November 20, 2009 | New York Times

Now that unemployment has topped 10 percent, some liberal-leaning economists see confirmation of their warnings that the $787 billion stimulus package President Obama signed into law last February was way too small. The economy needs a second big infusion, they say.

Saturday, November 21, 2009

Poll: 26 percent of Americans self-identify as kooks

Ab-so-lute-ly amazing.

November 19, 2009 | TPMDC

The new national poll from Public Policy Polling (D) has an astonishing number about paranoia among the GOP base: Republicans do not think President Obama actually won the 2008 election -- instead, ACORN stole it.

This number goes a long way towards explaining the anger of the Tea Party crowd. They not only think Obama's agenda is against America, but they don't think he was actually the choice of the American people at all! Interestingly, NY-23 Conservative candidate Doug Hoffman is now accusing ACORN of stealing his race, and Fox News personalities have often speculated about ACORN stealing the 2008 Minnesota Senate race for Al Franken.

The poll asked this question: "Do you think that Barack Obama legitimately won the Presidential election last year, or do you think that ACORN stole it for him?" The overall top-line is legitimately won 62%, ACORN stole it 26%.

Among Republicans, however, only 27% say Obama actually won the race, with 52% -- an outright majority -- saying that ACORN stole it, and 21% are undecided. Among McCain voters, the breakdown is 31%-49%-20%. By comparison, independents weigh in at 72%-18%-10%, and Democrats are 86%-9%-4%.

Now, the obvious comparison would be that many Democrats felt that George W. Bush didn't legitimately win the 2000 election. But there are some clear differences.

First of all, Al Gore empirically won the national popular vote in 2000, and lost in a disputed recount process in Florida. By comparison, John McCain lost the national popular vote by a 53%-46% margin.

In order to believe that Obama wasn't the true winner of the 2008 election, one would have to think that ACORN (and perhaps other groups) stuffed ballots to the tune of over 9.5 million votes, Obama's national margin.

PPP communications director Tom Jensen says: "Belief in the ACORN conspiracy theory is even higher among GOP partisans than the birther one, which only 42% of Republicans expressed agreement with on our national survey in September."

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Sarah won't rule out a Palin-Beck ticket, you betcha!

[Yeah, he's very effective at self-promotion, a quality which Palin surely admires. - J]

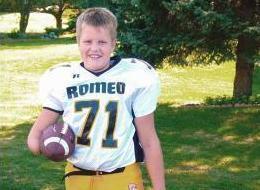

BCBS denies boy new prosthetic arm

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Another year, another record for Army suicides

November 18, 2009 | CNN